Plato: The Philosopher Who Shaped Western Thought

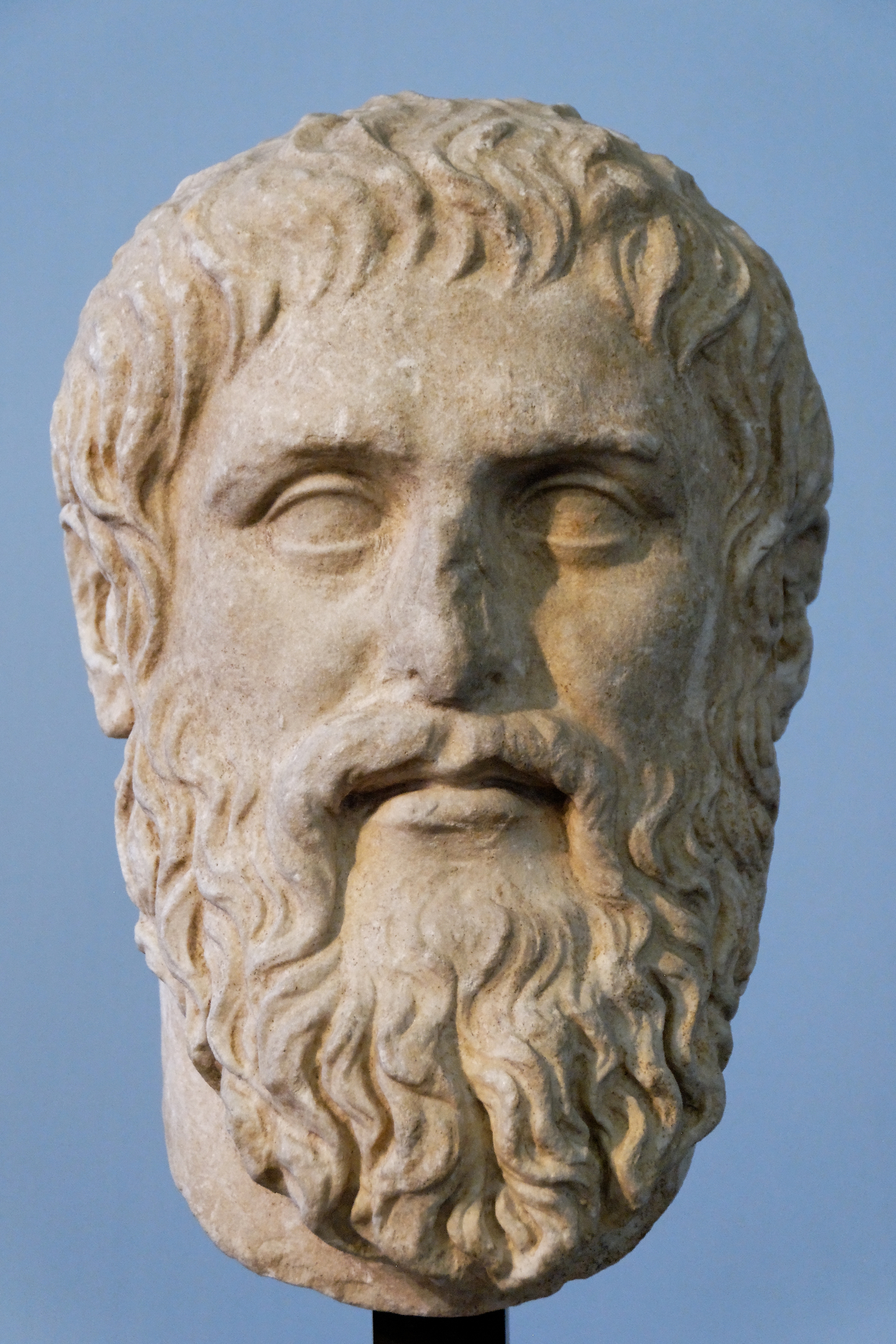

Classical bust of Plato, Roman copy of a Greek original

Plato (428/427 BCE - 348/347 BCE) stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of Western philosophy. Born into an aristocratic Athenian family during the Classical period of Ancient Greece, his work would go on to form the foundations of Western philosophical thought for over two millennia.

As the student of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle, Plato represents the middle period in the triumvirate of ancient Greek philosophers whose ideas have irrevocably shaped our understanding of reality, knowledge, ethics, and politics. His Academy, founded in Athens around 387 BCE, is often considered the first Western institution of higher learning.

Through his written dialogues, Plato articulated a comprehensive philosophical system that addressed fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, virtue, and the ideal organization of society. His Theory of Forms, Allegory of the Cave, concept of the tripartite soul, and vision of philosopher-kings continue to be debated and considered by philosophers, theologians, and political theorists to this day.

"The unexamined life is not worth living." - Attributed to Socrates in Plato's Apology

Life and Historical Context

428/427 BCE

Born in Athens, Greece, into an aristocratic family. His father, Ariston, was said to be descended from the king of Athens, while his mother, Perictione, was related to the famous Athenian lawgiver, Solon.

c. 407 BCE

Meets Socrates and becomes his student. Plato would spend approximately the next 8 years learning from Socrates, a relationship that would profoundly influence his philosophical development.

399 BCE

Witnesses the trial and execution of Socrates, a traumatic event that shaped Plato's views on justice, democracy, and the role of philosophy in society.

399-387 BCE

Travels extensively after Socrates' death, possibly visiting Egypt, Italy, and Sicily, where he becomes involved with the court of Dionysius I of Syracuse and his brother-in-law, Dion.

c. 387 BCE

Returns to Athens and founds the Academy, considered the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. The Academy would operate for nearly 900 years until it was closed by Emperor Justinian I in 529 CE.

367 BCE

Travels to Syracuse at Dion's invitation to tutor Dionysius II, hoping to create a philosopher-king. The experiment fails, and Plato narrowly escapes with his life.

348/347 BCE

Dies in Athens at approximately 80 years of age, having spent the last decades of his life teaching at the Academy and writing his later dialogues.

Plato lived during a turbulent period in Athenian history. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) ended with Athens' defeat by Sparta, leading to the brief rule of the Thirty Tyrants. Democracy was subsequently restored, but it was under this democratic government that Socrates was tried and executed, an event that likely influenced Plato's skepticism toward democracy as expressed in his Republic.

The intellectual climate of Athens during Plato's lifetime was rich and diverse, with competing schools of thought including the Sophists, who taught rhetoric and relativist views of truth; the followers of Heraclitus, who emphasized constant change; and the Eleatics, led by Parmenides, who argued for unchanging reality. Plato's philosophy can be seen as a response to and synthesis of these various intellectual currents.

Major Works and Philosophical Contributions

Plato wrote extensively, primarily in the form of dialogues where characters—often including Socrates—discuss philosophical questions. These works are usually classified into early, middle, and late periods, reflecting the development of Plato's thought.

Early Dialogues (Socratic Dialogues)

These works are generally thought to represent Socrates' own views and methodology rather than Plato's mature philosophy. They focus on ethical questions and typically end in aporia (a state of puzzlement), without definitive conclusions.

- Apology: Socrates' defense speech at his trial

- Crito: Examines the nature of justice and obligation

- Euthyphro: Questions the nature of piety

- Laches: Explores the concept of courage

- Charmides: Investigates temperance/moderation

Middle Dialogues

In these works, Plato develops his distinctive metaphysical and epistemological theories, including the Theory of Forms. Socrates remains the main character but now expresses views that are more clearly Plato's own.

- Republic: Plato's masterwork on justice, the ideal state, and the theory of Forms

- Phaedo: Discusses the immortality of the soul

- Symposium: Explores the nature of love

- Phaedrus: Examines rhetoric, love, and the soul

- Meno: Investigates virtue and introduces the theory of recollection

Late Dialogues

In his later works, Plato revisits and sometimes revises earlier ideas, often with a more technical approach. Socrates plays a smaller role, sometimes replaced by the Eleatic Stranger or Timaeus as the main speaker.

- Timaeus: Presents Plato's cosmology and natural philosophy

- Critias: Contains the story of Atlantis

- Sophist: Examines being and non-being

- Statesman: Discusses political leadership

- Laws: Plato's final work, presenting a more practical political vision than the Republic

Key Philosophical Concepts

Theory of Forms

Perhaps Plato's most famous contribution, the Theory of Forms posits that the physical world is merely a shadow or imperfect copy of the realm of Forms (or Ideas), which are eternal, unchanging, and perfect. For example, all beautiful things in the world participate in the Form of Beauty itself. The highest Form is the Form of the Good, which illuminates all other Forms.

This theory addresses the problem of universals—how can we recognize the same quality (like "roundness" or "justice") in different particular instances? For Plato, it's because these particulars participate in the same universal Form.

Epistemology and the Theory of Recollection

Plato believed that knowledge is not acquired but recollected. In the Meno, Socrates demonstrates that an uneducated slave boy has innate knowledge of geometric principles. Plato suggests that the soul, before being embodied, dwelled in the realm of Forms and retains this knowledge, which learning serves to uncover.

In his famous Allegory of the Cave (Republic, Book VII), Plato illustrates the journey from ignorance to knowledge as analogous to prisoners in a cave who only see shadows on the wall, eventually being freed to see the real objects, then the sun (representing the Form of the Good).

Psychology and the Tripartite Soul

In the Republic, Plato divides the soul into three parts:

- Rational (Logistikon): The thinking part, which seeks wisdom and truth

- Spirited (Thymoeides): The passionate part, which seeks honor and courage

- Appetitive (Epithymetikon): The desiring part, which seeks physical pleasures

Just as the ideal state is governed by philosopher-kings, the well-ordered soul is governed by reason, with the spirited element as its ally in controlling the appetites.

Political Philosophy

In the Republic, Plato designs his ideal state, which is structured like the tripartite soul:

- Guardians (Philosopher-Kings): The rulers, representing the rational soul

- Auxiliaries: The warriors and enforcers, representing the spirited element

- Producers: The farmers, artisans, etc., representing the appetitive part

Plato was critical of Athenian democracy, which he saw as rule by the ignorant and emotionally driven masses. He favored an aristocracy of the wise—his philosopher-kings, who would rule not out of self-interest but with knowledge of the Forms, especially the Form of the Good.

In his final work, the Laws, Plato presents a more practical political vision, recognizing the challenges of implementing the ideal state described in the Republic.

Plato's Legacy and Influence

It would be difficult to overstate Plato's influence on Western thought. Alfred North Whitehead famously remarked that "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."

Philosophy

Plato's work established many of the central questions and methods of Western philosophy. His dialogues shaped how philosophy is practiced and taught. The division between idealism and materialism in philosophy largely stems from reactions to Platonic thought.

Religion and Theology

Neo-Platonism, developed by Plotinus in the 3rd century CE, adapted Plato's ideas into a religious philosophy that influenced both Christianity and Islam. Christian theologians like Augustine and Aquinas incorporated Platonic concepts into Christian doctrine.

Science and Mathematics

Plato's emphasis on abstract reasoning and mathematical principles influenced the development of mathematics and theoretical sciences. The sign allegedly at the entrance to his Academy—"Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here"—reflects his view of mathematics as crucial to philosophical thinking.

Politics and Social Theory

Plato's political philosophy has influenced both utopian thinking and critiques of democracy. His concept of philosopher-kings resonates in various forms of enlightened despotism and technocracy, while his critiques of democracy remain relevant in discussions of its limitations.

Major Schools of Thought Influenced by Plato

| School/Movement | Period | Key Platonic Influences |

|---|---|---|

| Neo-Platonism | 3rd-6th century CE | Theory of Forms, concept of the One (the Form of the Good) |

| Christian Platonism | 3rd-5th century CE | Immortality of the soul, transcendent reality beyond the physical |

| Renaissance Humanism | 14th-17th century | Revival of Platonic texts, Platonic Academy in Florence |

| Cambridge Platonists | 17th century | Rational theology, innate ideas |

| German Idealism | 18th-19th century | Idealism, focus on rationality and the absolute |

| Analytic Philosophy | 20th century | Logical analysis, problems of language and reality |

Even those who explicitly reject Platonic metaphysics often do so within a framework established by Plato's questions and methods. His influence extends beyond philosophy into literature, political theory, educational theory, and even modern fields like cognitive science and artificial intelligence, which grapple with questions about the nature of mind and knowledge that Plato first articulated.

Criticisms and Contemporary Perspectives

While Plato's influence is undeniable, his ideas have not gone unchallenged. His student Aristotle was the first significant critic, rejecting the separate realm of Forms in favor of finding universals in particulars. Later thinkers have raised additional criticisms:

- Elitism: Plato's political vision in the Republic has been criticized as authoritarian and elitist, with its rigid class structure and rule by philosopher-kings.

- Dualism: His sharp division between the physical and ideal worlds has been challenged by materialists, pragmatists, and others who reject metaphysical dualism.

- Anti-democratic views: His critique of democracy, while based on legitimate concerns about mob rule and demagoguery, has been seen as too dismissive of democratic principles.

- Gender and class biases: Despite being progressive for his time in allowing women to be guardians in his ideal state, many of Plato's views reflect the hierarchical and patriarchal assumptions of ancient Athens.

Contemporary interpretations of Plato are diverse. Some scholars emphasize the literary and dramatic aspects of the dialogues, seeing them less as systematic doctrine and more as philosophical explorations. Others focus on the development of Plato's thought across the early, middle, and late dialogues, noting significant shifts in his positions.

The resurgence of virtue ethics in the late 20th century, led by philosophers like Alasdair MacIntyre, has brought renewed attention to Platonic and Aristotelian ethical frameworks. Similarly, contemporary political philosophers continue to engage with Plato's critiques of democracy and his vision of expert rule.

Recommended Reading on Plato

Primary Sources

- For beginners: Apology, Crito, Euthyphro, Meno, Symposium

- For intermediate readers: Republic (especially Books I, II, IV, VI, VII), Phaedo, Phaedrus

- For advanced study: Timaeus, Sophist, Parmenides, Theaetetus, Laws

Secondary Sources and Commentaries

- Gregory Vlastos, Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher

- Julia Annas, An Introduction to Plato's Republic

- Terence Irwin, Plato's Ethics

- Francis Cornford, Plato's Theory of Knowledge

- Alexander Nehamas, The Art of Living: Socratic Reflections from Plato to Foucault

- Roslyn Weiss, Virtue in the Cave: Moral Inquiry in Plato's Meno

- Charles Kahn, Plato and the Socratic Dialogue